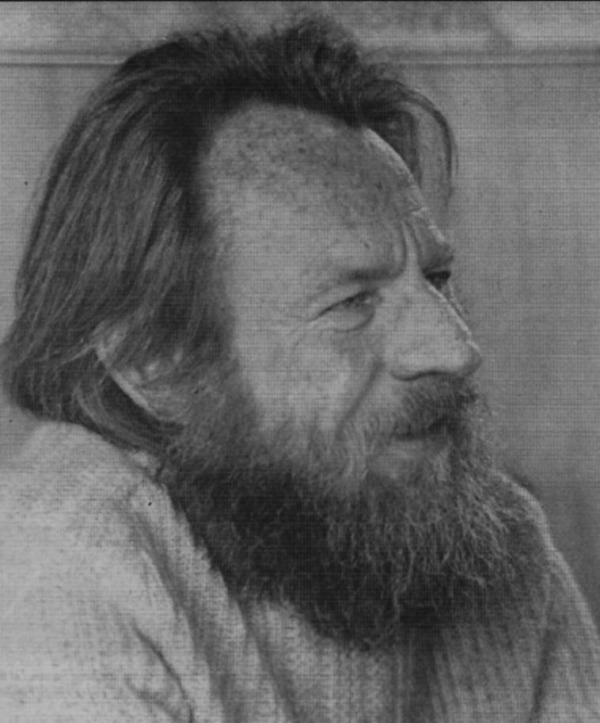

John Spencer

John Spencer (1931 - 1996) - Javelin Class Designer

As most of you will be aware John Spencer, the designer of the Javelin died in 1996.

I thought it would be appropriate to have something to remind us of the man behind the class.

"A brilliant designer and superb craftsman, John's lifelong passion was to get as many people as possible particularly youngsters - onto the water in their own affordable boats."

"Knowledgeable in many areas, complex and multi-talented, well-read, or quick mind and keen humour, popular and generous, many believe that only Johns modesty and dislike of publicity kept him from being a national hero."

"He was the champion of the amateur boatbuilder. Next to affordable, his boats had to be simple and fun. They were always fast." "In his final years John returned to his roots - to his affinity for small boats, dinghies which kids could build with their parents. Earlier generations had grown up with Spencers Flying Ant, Cherubs, Javelins and Frostplys. Now kids and their parents were discovering his Jollyboats, Firebugs and Firebirds."

"In his final years John returned to his roots - to his affinity for small boats, dinghies which kids could build with their parents. Earlier generations had grown up with Spencers Flying Ant, Cherubs, Javelins and Frostplys. Now kids and their parents were discovering his Jollyboats, Firebugs and Firebirds."

"Internationally John is best remembered for his series of radically fast, lightweight but strong keelboats. Yachts like Infadel (now Ragtime), Buccaneer, New World, Whispers II, Sirius and many others changed forever the old concepts of a performance off-shore sailboat."

"More than anything in his life, John abhorred 'bullshit'. Expensive ways of doing things which could be done as well, if not better, in an affordable way were the worst 'bullshit' of all."

Timeline, of the Javelin design

"1957-58 - The Javelin was designed along with a "much-improved" Cherub."

"1960 - More cherubs on the water, an improved Javelin and new keel boats"

"1962 - He was building a number of Javelins, Cherubs and powerboats up to 6.7m"

Prolific Letter Writer

"John was a prolific letter writer, often sending and receiving as many as 17 letters in a day, to and from all corners of the world."

Some excerpts from his more than 300 letters to Peter Tait:

"One and a half weeks to go to the pension. Will believe it when I see it on the bank statement. I wonder if they pay it before or after. I suppose they would not pay it in advance in case you dies before the fortnight was up."

"Social Welfare department informed me today that my first 'guaranteed' retirement income will be deposited in my bank account tomorrow and henceforth every 2nd Tuesday. I brought after much hesitation this afternoon, a plastic bottle of $19.95 gin to celebrate. It is as good as any other London Dry but had one and decided I had lost my taste for it. I guess it's all just habit but why can't I get a habit for fruit juice?"

Reproduced with permission. - Boating New Zealand, April 1996

A Fresh Perspective

The following article was written by John Spencer in Boating New Zealand magazine at the time the Javelins moved to the new style Main and Jib sail plan. It provides an interesting history to the early days of the class and sail measurement ideas.

Efficient rig design proves essential

While the 'least said, soonest mended' of Peter Blake's unfortunate remarks in mid March, I was intrigued by the report that Sir Tom Clark had said of NZL 20 that she looked like an 'ugly Infidel.'

Now there is a comment, no doubt made 'off the cuff', that could be interpreted to mean several things which I am sure Sir Tom did not intend. I'm quite sure that he was thinking back to those glorious days of the 1960s when the 'Black Box' could lose a race but didn't do so very often. Some have called NZL 20 'ugly', just as some said the same of Infidel.

To me NZL 20 is a beautiful creation, which is what Cove Littler, owner of Ariki said of Infidel back in the mid 1960s. Maybe that's what Alan Sefton had in mind when he said NZL 20 looked like a modified Spencer design. She is not, of course, except in that she is an exciting boat, as Infidel was here in the 1960s and later Ragtime in California.

I have already commented on the skiff type rig and sail plan design that we are seeing in the new America's Cup Class. It is obviously very efficient so we might well wonder why it never happened before or why it took so long to happen. The fact is that it has all happened before, as long ago as 60 years, but has been inhibited by rules that prevented real development and only really encouraged rule beating. Two things are involved in designing a really efficient sail plan and both were proven before most of us were born. Both in fact could be said to have been proven by the schooner America, back in 1851.

Even 100 years later the thinking of rulemakers was based on the assumption that the effective area of headsails was 80 per cent of the area between the forestay and the mast and classes such and the International 6 and 12 Metre still use that formula, as indeed International 14s still did many years later. Consequently the actual area of a headsail could be more than double the measured area.

In America's day jibs overlapping the mast were unthinkable but a cutter-rigged fore triangle did allow extra sail area due to the overlapping jibs and staysails. It was generally agreed 100 years later that cutters were about two per cent slower upwind anyway as they couldn't point as high as a sloop due to this.

It was around 80 years after America that a Scandinavian 6 Metre fronted up for the class championships in Genoa, Italy, with an overlapping jib of considerably greater area than it measured. It became known thus as the genoa jib. Previously an American 6 Metre had been designed with a smaller mainsail and a wide non-overlapping jib set on a boom, much like America's single jib. The rulemakers, for some incredible reason didn't like that but allowed the genoa jib to continue, with no measurement of the additional area. This form of measurement was adopted for Ocean Racing Rules and persists to this day. If you don't have a genoa you have less sail area but no less measured area.

The other thing America proved was that you need sails that hold their shape. She raced with cotton sails that stretched far less than the flax sails that were used in those days. Now we have mylar, kevlar, and some into experimenting with carbon fibre, replacing dacron woven polyester because it stretches less, just as dacron stretched less than cotton and became the material to use some 30 years ago.

50 years ago it was being well proven that in modern rigs overlapping sails were slow if the full area of a headsail was measured. When the Star Class, designed in 1911 introduced a new sail plan in 1930, they went for what later proved best in the Redwing Class in England which had one design hulls but allowed freedom to design the best possible sail plan within a maximum area.

The Soling Class has much the same, designed 30 years later and the Star Class's 1930 sail plan is as efficient as any designed today unless allowed full length battens to support more roach area.

Full length battens are nothing new. Few things are. Canoe sailors had them 100 years ago and called them 'batwing' sails. A low mast and large roach held out by three battens gave them an efficient sail with less weight and windage up high on their tender craft. The Chinese had them on their junks some 2000 years BC, that is 4000 years ago. They also had suction bailers made from bamboo.

Large roach also has been prevented by rulemakers since the gaff sail became unfashionable. It is also, of course inhibited by the desire of most sailors today to rely on a standing backstay to hold up the mast.

The masthead rig developed as a result of rules that gave it more free area and allowed it much larger spinnakers. The original sail plans for Beven Wooley's Sabre and Tom Clark's Saracen had no standing Pied Piper. Their rigs worked fine without, even for family cruising and were the forerunners of the admittedly more complicated America's Cup Class rigs we see now; dinghy rigs.

The efficiency of a larger roach, fully battened mainsail is not, however based on free area that is not measured and nor is it unseamanlike.

Some cruising sailors still prefer the gaff rig for it enables them to set a lot of area on a relatively short mast. The Chinese junk rig has even been preferred by some ocean racing sailors, such as Blondie Haslar for similar reasons. Full length battens can be used to achieve the same in a modern sail but most sailors today feel uncomfortable without a standing backstay which can fully support the mast aft. Despite this we are seeing more and more fractional rigs in which the standing back-stay does no more than control mast bend while the mast is held up aft by runners, as in the early days of gaff rigs and long booms. Runners in fact are often needed on today's masthead rigs.

Measuring mainsails was, and often still is thought to be simplified by measuring only the triangle between the three corners or, in the case of a gaff sail as two triangles. Usually this was further simplified by using only the luff and foot measurements. Roach area was not measured as it was supposedly restricted by limiting the number and length of the battens.

Very conservative

Traditional sailmaking methods certainly did not allow much roach to set well with short battens but even in New Zealand, where full length battens were commonly used, far more was possible than was mostly seen. Traditional sailmakers were very conservative but in the 1950s dinghy sailors such as Paul Elvtrom, Bruce Banks and Rolly Tasker got into making their own sails and from success there went into business as sailmakers. The pressure they put on measurement rules with larger and larger roach areas resulted in the introduction of cross measurements to contain this; in some classes full length top battens were used as well to support the top of the sail better where the process had already gone too far.

We all like the idea of simple measurement rules but simple to measure can often mean simple to beat and gain extra area. This applies particularly when full length battens are allowed and has been experienced in some classes. Crosswidth measurements at quarter, half, and three quarter heights with measurement bands on the mast and boom had evolved by 1960 as the popular way of ensuring that one design or restricted class sails were all of equal area. It didn't work! IYRU eventually decided that the position of the measurements should be determined by folding the leach, not the luff, and that was a big improvement for one design sails, which is what it was intended for.

For restricted or development classes IYRU recommends measurement of total area unless class rules say otherwise. The Australian skiff classes and NS 14 dinghy use full and total area measurement methods where there is a maximum sail area stipulated and don't seem to have any problems with the arithmetic involved.

The luff times the foot, divided by two, is not the actual area unless the boom sets at 90 degrees to the mast. Droopy booms are not some break-through in sail design, only another way of getting more sail area. If it might endanger a head or two in the cockpit that's the risk you must take to have an advantage, unless you are fortunate enough to be sailing in a class that has good measurement rules. The rules don't have to be one design ones for sails and, until we get the sailors all cast in the same mould I don't even think true one design sails are the answer for equality.

In the America's Cup we see now the crew being weighed, as well as the yacht when a measurement check takes places. Could we live with a dinghy class that had rules restricting our height and weight so that we were in fact all equal?

Some dinghy classes have a very small margin of weight tolerance, partly due to the boat length being short and often the result of the designed shape in a one design; its sail area and sail plan also likely to affect this. Certainly it would seem that the long accepted principle of weight is important.

Uffa Fox once said that weight is no use except in a road roller. He wasn't thinking of crew weight, which certainly paid dividends in the International 14s of his design at that time in the 1930s.

Many classes have been concerned over the advantage to lightweight sailors in dinghies of 12 or less feet in length, some even longer for the Pheonix Class was among the first to be concerned with this and is 4m in length. Other classes of maybe more length and certainly more sail area have been concerned over the need for a lightweight skipper and heavy crew.

All classes today seem very concerned as to their popularity and more getting out than are coming in, nationally. I think that it is, either way a matter of development. If a class does not develop it will very likely stagnate. If, on the other hand it out develops too many existing hulls then these have to be replaced, which is not so easy to do. If, on a further hand (how many do we have?) the sail plan is allowed to be developed we are talking something that is regularly renewed, as long as it means only the sails and not the full rig.

Skiff sails, with no real restrictions other than area and not even that in the 12s, have become the leaders of the world and yet almost one design. What I am driving at is that with freedom to choose, in a dinghy class that does restrict the sail area, the same area should be allowed to a lighter crew if they choose to have a lower rig. If the height of the rig is restricted to being moderate or low the heavier crews will be less disadvantaged by small sail area if it is allowed to be efficiently used higher up, and if this suits all the class will end up well ahead of others.

Javelin rigs

I would like to have seen the Javelin Class's new sail measurement rules allow lower rigs of the same area for I'm quite sure that this would have been good for the class now it has updated its sail plan. The very simple measurement procedures now adopted would not have been compromised by allowing this.

I promised more about that and here it is. It has been tough getting to this with my deadline and poor ability on a typewriter competing against the excitement in San Diego and real dinghy racing stuff to watch in the semifinal series for both challenger and defender.

The Javelin Class was created from the wishes of sailors such as Helmar Pederson and Ian Pryde, and others from the Cherub class who saw the need for a bit more length and sail area for the crew weight they had. Ian Pryde, like myself earlier had built and raced an International 14 and had experience of that class. His was also a Kiwi design, by Des Townson.

The 14s were a great boat but not one that appealed to most Kiwi sailors. A heavy, by our new standards, minimum weight, minimal buoyancy to penalise those who capsized or became swamped as a result of decks restricted to a 3inch gunwale, trapezes not allowed and an ineffective spinnaker due to the short spinnaker pole allowed, all pointed towards a Cherub Type 14 being faster and more exciting to sail with less sail area and consequently less cost.

What with the 1960 Olympics and the advent of the Flying Dutchman as the Olympic two-handed class the Javelin sat there, its rules formulated, while its main proponents chased Olympic selection.

A couple were built to a design I had drawn earlier as a Y Class, which fitted the rules but had sufficient rocker to be fast with a three-handed crew. I built Javelin number 3 from a design originally intended as an International 14 for a lightweight crew and this got the class going in Auckland, after being the show in John Burns and Co's ship chandlery window downtown in Commerce Street.

I was then asked to produce a further design, to the limit of the rules and based on the Mark 6 Cherub design, for heavier sailors. This design, for various reasons became known as the Mark 1 Javelin and my earlier design as Mark 2. The Willetts Memorial Trophy, now raced for exclusively by Javelins was then seen as the Auckland Provincial 14 Championships and at that time the International 14s had shown superiority over all other 14ft classes.

In their first season, with only two or three completed the Javelins won the trophy and the following year seven Javelins entered, filling the first seven places. All used wooden bendy masts, mostly made by me. These were relatively stiff by later standards when aluminium masts took their place and had little, if any, pre-bend.

The first rig development in the class came from Murray Ross. Murray developed a rig that had a lot of pre-bend and mainsail cut to suit this. The Javelin, like the Cherub was given a development hull design rule but one design sails, with cross measurements to control it from the start.

What began as a generous amount of roach however, with Murray's rig development had to be used in the luff and particularly at half height. Thus sails became straight or even hollow in profile on the leach, with a kickback at the top and bottom to the masthead and boom. Murray's ability to get power from such a rig made the team of Biger and Ross virtually unbeatable but most found Javelins going slower and lacking power.

Eventually the penny dropped and larger sections for masts replaced the very thin ones Murray had introduced, though still only what Cherubs had been using all along. Pre-bend was still considerable and Javelin sail plan rules made it difficult to get a nice looking efficient mainsail.

The next development was high foredecks. You may well ask what that has to do with the rig but Javelin rules, like many others over the years, limit the height of the rig from the deck instead of the sheer, or did until recently. Javelins were getting a reputation for needing a midget to steer them and a gorilla for crew. A gorilla needs more room under the boom to get quickly from one trapeze to the other so, with plenty of weight to handle the additional leverage from a mainsail up higher is even further advantaged if others do likewise.

By then this was getting the spinnaker and jib all out of kilter for the forestay and spinnaker hoist were now also much higher than on our original Javelins for which the sails were designed. They looked, in fact like they had got borrowed off a Cherub and even Cherubs had seen problems with their rig developments, adopting a new sail plan several years later.

It was the Victorian Javelin Association which made the initial effort towards a new sail plan, concerned over their windward performance against NS 14s being poor despite the Javelin's trapeze and 6 per cent more sail area. This probably had been the cause of the Javelins becoming almost extinct in New South Wales.

Melbourne sailor Wayne Gelly saw the Cherubs adopting a new sail plan to their advantage and felt the time had come for Javelins to do the same. After consulting with me he had a prototype set made and took them to the South Pacific Championships in Perth, January 1987, where 11 Kiwi Javelins competed with Cooltainer sponsoring freight costs to and from the event.

Nothing much happened but further discussion at the 1988 Sanders Cup brought the Wellington Javelin Squadron, at that time Head Office for New Zealand, and Warren Wolfie Williams to pressing for a development type measurement rule that would allow improved sail design within the existing rig and individual sail areas, allowing replacement of one sail at a time. I was eventually asked by Wolfie to write the rules and did so one the basis of an area measurement.

Further discussion between New Zealand the various Australian State associations determined that owners preferred a more simple measurement procedure and with a 75 per cent majority needed to pass any rule change it became a challenge to find, somehow a simple method that would not contain loopholes. A number of people, both here and in Australia finally put together a rule that looked good and it got the almost unanimous support of owners in both countries to become effective for the 1991-1992 season.

The new jib, close to 1m longer on the luff, fits the rig far better and the shorter foot length eliminates most of the overlap, allowing sheeting further forward which gives crews more room to operate. It also allows narrower sheeting and higher pointing so, as I would have expected became a must.

As we are seeing in the America's Cup, if you can point higher, maintain boat speed and tack quickly, you have got it right. The new jib does all three. After a season's racing there seems no doubt that the new mainsail is also superior to the old when it comes to boat speed, even if the difference is less dramatic and it certainly looks like the new sail plan has put the Javelin back to being the ultimate two-handed single trapeze dinghy.

The very simple measurement arithmetic, which in the past could certainly have been vulnerable, becomes very effective in controlling area in a large roach mainsail and also evident seems to be Ken Fyfe's position as the top sailmaker for the class over this past season. Ken's experience in skiff and Cherub sails of this type had to count and his expertise is well known in there.

The Javelin looks really set now for the 1990s and beyond, both here and in Australia. It's a class where, despite its development rules, older designs and older hulls still hold their own at championship level. There are no problems with its rules there and never have been.

Maybe next month I should write more of design development in dinghies generally and why older designs are remaining competitive in the Javelin Class.