Sanders Cup History

Battle for the "Prize"

Sanders Cup articles courtesy of Robin Elliot and Harold Kidd

In April 1916, Sub Lieutenant W.E. Sanders (a New Zealander serving with the RNR) joined HMS "Sapina" as Second in Command. When a year later Q ships were adopted as a means of combating the submarine menace Sanders volunteered for service and was given command of the Topsail Schooner "Prize" and promoted to Lieutenant-Commander.

On the evening of April 30th, 1917 the "Prize" was 120 miles south of Ireland when they spotted a U93 running awash. The submarine opened fire from 4000 yards sending her first shells well over the schooner. As a courtesy gesture, at this the schooner lowered her topsails and a well drilled "Panic Party" manned their boat and pushed off. Sanders and his gun crews laid hidden waiting for the submarine to come close, however the German commander was suspicious and kept firing as he closed in, reducing the "Prize" to a mass of wreckage.

On the evening of April 30th, 1917 the "Prize" was 120 miles south of Ireland when they spotted a U93 running awash. The submarine opened fire from 4000 yards sending her first shells well over the schooner. As a courtesy gesture, at this the schooner lowered her topsails and a well drilled "Panic Party" manned their boat and pushed off. Sanders and his gun crews laid hidden waiting for the submarine to come close, however the German commander was suspicious and kept firing as he closed in, reducing the "Prize" to a mass of wreckage.

Sanders and his men stuck to their posts as shell after shell battered the hull. During this time Sanders was perfectly cool and occasionally crept forward on his hands and knees to visit the forward gun crews and ascertain how they were withstanding the shell fire.

Finally convinced the schooner was in sinking condition the Germans ceased fire and steamed close to get the ships particulars. Sanders decided the moment he had waited forty minutes for had come and with a blast from his whistle the gunscreens clanged down, the white ensign fluttered up the mast and the "Prize" opened fire. The first salvo disabled the submarines forward gun. She turned and ran preparing to dive while three men manned the after gun only to be sent swimming by the "Prizes" shells. The submarine was last seen settling in the water stern first, her bow straight up in the air.

Severely damaged the "Prize" limped to port carrying with her the German U boat commander and others rescued from the water.

Sanders was awarded the V.C. on June 27. 1917 but never lived to receive it as the "Prize" was sunk with all hands on August 14, 1917 by a torpedo from a German U Boat.

For his services in this action, Sanders was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Order.

Part 1: The 14-foot One Design

Apart from those few hardy souls racing in the14-foot Javelin class, the Sanders Cup is mostly unknown to today's yachtsmen. It is still the ultimate goal in the Javelin national calendar, but for the rest of New Zealand, the event passes with barely a whisper.

It was not always so.

There was a time when the Sanders Cup was the ultimate prize in New Zealand yachting, and its raison d'etre, the 14-foot X-class (also known as the Jellicoe Class), was the ultimate New Zealand centreboarder nationwide. Nothing else matched them.

Such was its stature, that for almost forty years, newspapers around the country devoted as much space to the Sanders Cup in summer, as the Ranfurly Shield during winter. Details of who was racing in the local trials, the winners, the losers, and the unlucky, followed by tack for tack descriptions of each Sanders Cup race, province against province, were eagerly read by yachtsmen all over New Zealand.

The Sanders Cup elite, George Andrews, Billy Rogers, Peter Mander, Graham Mander, and all the other top-notch regional skippers who competed for it, were giants in their day and tremendous influences on their peers. To aspiring youngsters, they were heroes but at the same time, were yacht club regulars who rigged up alongside everyone else, you could see them most weekends, speak to them, watch them set up their boat, watch them race. By comparison, many of today's yachting icons, having gained their (quite justifiable) nationwide recognition on an international stage, seem somewhat remote. The Sanders Cup in its heyday was New Zealand yachting through and through. The rest of the world did not matter.

The competition had its origins well back before the First World War. Following the demise in 1904, of New Zealand's first centreboard class, the 18ft 6in Restricted Patiki (See Vintage Viewpoint August 1998), there were a number of moves to establish another modest centreboard class to attract young men into the sport. Little happened until 1908 when the Waitemata Dinghy Club was formed as an offshoot of the Devonport Yacht Club. For several years, this club held races for their restricted design 14-foot and 10-foot dinghies, but by 1912, WDC had gone into recess (most of its better dinghies had found a new home in, of all places, Kawhia).

The competition had its origins well back before the First World War. Following the demise in 1904, of New Zealand's first centreboard class, the 18ft 6in Restricted Patiki (See Vintage Viewpoint August 1998), there were a number of moves to establish another modest centreboard class to attract young men into the sport. Little happened until 1908 when the Waitemata Dinghy Club was formed as an offshoot of the Devonport Yacht Club. For several years, this club held races for their restricted design 14-foot and 10-foot dinghies, but by 1912, WDC had gone into recess (most of its better dinghies had found a new home in, of all places, Kawhia).

W.A.`Wilkie' Wilkinson, in his magazine, the New Zealand Yachtsman, was a regular champion of the smaller boats and again called for the re-establishment of `a small dinghy class suitable for young boys'. His proposed `Yachtsman 14-foot Dinghy' was even backed by the offer of a completed 14-footer from Ernest Davis as a prize. Apart from a lot of talk, nothing much happened, although from time to time over the next four years his editorials peevishly brought up the topic, and complained about yachtsman's apathy in general.

As well as influencing the yachting public through N.Z. Yachtsman, the energetic Wilkinson was also commodore of the powerful North Shore Yacht Club and did not readily let go of his `pet' projects. On 23 October 1916, he submitted plans to the Auckland Yacht and Motor Boat Association for a smart little clinker 14-footer, drawn by Glad Bailey, son of Charles junior, and asked that they adopt it as a strict one design class. Within a month most clubs had agreed in principle, although perversely, Richmond adopted it unrestricted, Ponsonby and Manukau adopted it undecked, while North Shore's fierce rivals, Victoria Cruising Club ignored it altogether.

With so much indecision, North Shore Yacht Club, under Wilkinson's direction, went ahead and adopted the design as it stood. He then announced that Bailey was building a 14-footer to the plan for Messrs Frank Cloke and Joe Patrick, owners of the crack 24-foot linear rater Speedwell. The first 14-foot One Design was named Desert Gold (after a famous racehorse of the time), and launched in January 1917. Like Speedwell, she carried a huge red star on her mainsail, an indication of her owner's strong socialist leanings. She was joined a few days later by another, La Ola, built by the Ross brothers of Orakei.

In the 1917 Auckland Anniversary Regatta, Desert Gold easily beat La Ola and Dixie, the last of the old WDC dinghies, and went on to win every race she entered that season. She dominated all 14-footers in 1917/18 season as well, and then for reasons unknown, was laid up.

Despite such a clear superiority over existing 14-footers, there was little interest in a new yacht class. The Great War in Europe was grinding to a close and yachting, like many other sports was still in limbo.

The 1918/19 season however saw the arrival of Betty, built by Walter Bailey and sailed by Norm Bailey. Like Desert Gold, Betty trounced any opposition and won both line and handicap in the 1919 Regatta. Among the opposition that day was George Honour in a chunky new square-bilge 14-footer named Sasanof, to whom Betty was giving 12 minutes. This lengthy handicap stands in sharp contrast to Ronald Carter's florid prose in Little Ships wherein he described Sasanof, the prototype of the popular Y-Class, as being `light as a feather …..', and how she ` .. blew across the water light as a piece of thistle down'. Pity any wildlife downwind of that particular thistle. By the end of the season, Betty was giving Sasanof 17 minutes.

Desert Gold returned to racing in the 1919/20 season, and immediately went into a head to head battle with Betty. The arrival of another, Meteor sailed by T.G. Parker added spice to the racing and all other 14-footers were left in the wake of the three One Designs. They dominated the 1920 Anniversary Regatta, all three raced off scratch. Next lowest handicap in that event was George Honour's newest square bilge 14, Sea Sprite on 10 minutes handicap. More thistledown to endanger the local wildlife.

Post-war optimism, coupled with the social and economic changes that followed the end of World War I, fueled a boom in yacht club membership, yacht building and racing. It seemed the time was right for a new yacht class. Wilkinson was now shipping correspondent for the Auckland Star, and writing a weekly yachting column under the by-line `Speedwell'. He promoted the merits of the fledgling 14-foot class at every opportunity.

During the winter of 1920, the AYMBA approved the rules and restrictions for the 14-foot One Design Class, and guaranteed a period of 5 years before any further changes were to be made. Following this news, Wilkinson announced that inquiries had come `from all over New Zealand' and that `Mr. H.P. Nees of the Otago Yacht Club was in town and will take back with him full plans of the 14-foot One Design class'.

Over the next few months, he endlessly reported the building news in the 14-foot class. Certainly, from a standing start, it was impressive stuff. Eleven were under construction, for such famous names as Lidgard, Bailey, Wild, Ewen, Gifford and Endean, with others imminent. Wilkinson canvassed prominent Auckland yachtsmen and raised £30 for prize money to be won over ten races, a small fortune by today's standards. Even the august Royal New Zealand Yacht Squadron, who had previously ignored centreboarders altogether, announced its intention of holding an Under-21 series for its junior members.

Mind you, their main reason for being involved in the first place (and indeed the main reason for the sudden popularity of the new class) was the knowledge that New Zealand's incoming Governor General, Viscount Lord Jellicoe, was a keen yachting man. He had a preference for racing one-design class keelers, but at the time Auckland had no such class. Even so, he had indicated that he was prepared race smaller craft as long as they were `to a class design'.

The closest `class' racing Auckland had at the time was among the red-hot 22-foot mullet boats. They were providing the most exciting racing on the harbour, but to the RNZYS patricians, the mere thought of Jellicoe patronising the smoky working class clubs of Ponsonby and Victoria, instead of the Squadron, would have been too horrible to contemplate. The 14-foot One Design it had to be then.

The entry of the Squadron into the One Design fray was good for the class, as all Auckland yacht clubs were now involved in some form or another.

All was not rosy however. The predominance of boatbuilders among the new owners raised eyebrows among many older yachtsmen for whom amateurism was a requirement for all proper yachtsmen. At the 1920 AGM of the North Shore Yacht Club, Mr. F.W. Chalmers commented on the construction cost rising from £35 to £76 and that `… instead of being sailed and handled by boys, they were sailed by men, including a number of professionals who were not out for the love of the sport but for what they could get out of it.'

Any further discussion on such Edwardian niceties paled into insignificance on 6 November 1920 when Wilkinson breathlessly announced in the Star, that the Governor General, Viscount Lord Jellicoe, the hero of Jutland, had placed an order with Charles Bailey junior for a 14-foot One Design. Prominent Squadron member, W.P. Endean, already had one being planked at Bailey's, and sportingly offered to wait until another could be built, to allow Jellicoe to start the season on time. The new boat was a birthday present from Lady Jellicoe.

Any likelihood of the class being purely an Auckland affair now vanished completely. A governor-general has always been the closest to royalty we have ever had, and in the patriotic fervour of post-war New Zealand, to have one sailing his own boat, in club races, and a war hero to boot, was just too appealing. Everyone wanted to be seen with `the great man'.

|

| Model of the X-Class "Iron Duke", with the much newer Javelin "Night Nurse" in the Background |

_

The 1920/21 season opened to high expectations, and heightened further when the Otago Yacht and Motor Boat Association challenged their Auckland counterparts to a race to decide the championship of the 14-foot One Design class. Just how much Wilkinson had in engineering this is not known, but given his extensive contacts in the yachting community and the fact that he had been advocating just this sort of thing for well over ten years, it seems likely that he prodded his old Dunedin mates into a challenge.

Jellicoe's boat, named Iron Duke was launched Monday 13 December 1920. The following Saturday at the North Shore Yacht Club, skippered by Jellicoe, with designer and builder, Glad Bailey in his crew, she finished fourth. Both officials and contestants complained about wash from the large spectator fleet.

By New Year 1921, fourteen One Designs were racing in Auckland; six were building in Dunedin and one at Russell. The class was further elevated by news that Messrs. Walker & Hall Limited had donated to RNZYS (who then vested it in the AYMBA), a 50 guinea championship cup, open to all New Zealand. The cup was dedicated to the memory of Devonport born Lieut.-Com. W.E. Sanders V.C., D.S.O. R.N.R., lost on the Q-ship Prize in August 1917.

The first bout of national Sanders Cup fever was under way.

Part 2: From Jellicoe to Rona

Following the presentation of the Sanders Cup early in 1921 by Walker & Hall Limited,

`14-foot One-Design fever' now raged in both Auckland and Dunedin as trials were held to decide who should represent their province for the inaugural championship of New Zealand. Yachting columns in the national newspapers, and particularly `Wilkie' Wilkinson's in the Auckland Star, were now given up almost entirely to the 14-foot class.

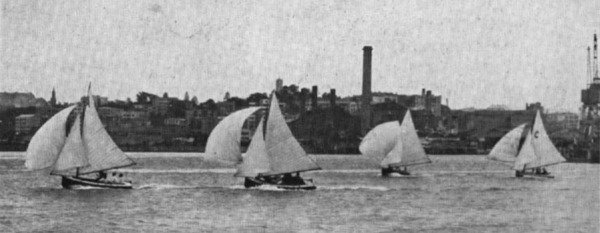

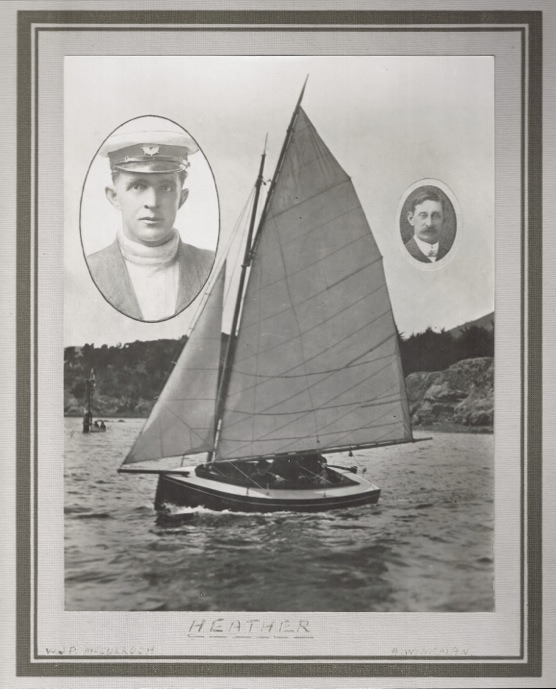

In Dunedin, trials between Heather, Squib, Valmai, Eunice and Gladys had resulted in Heather and Valmai being equal first after ten races. Valmai's owner withdrew allowing Heather to be sent north. In Auckland, it was Lord Jellicoe's Iron Duke that won through, despite some tough opposition from Nyria and Ola III. The prototype, Desert Gold, missed most of the selection trials.

At last the great day arrived. To Auckland's shock, Heather, skippered by her owner Bill McCullough, easily won the first race by 1m 14s, despite Iron Duke's professional crew of skipper Glad Bailey, George Tyler and George Dacre. But for a wind shift late in the race it would have been worse, for at one point, Heather was more than three minutes ahead.

Honour was somewhat satisfied the next day, when Iron Duke made the best of shifting breezes to win the second race, and did so again the following day, both with Lord Jellicoe at the helm. The next two races were in solid sou'westers, and again Heather showed the Aucklanders how to sail on their own harbour. She won the fourth race by a whopping 12m 25s and the deciding fifth race by 2m 7s.

Honour was somewhat satisfied the next day, when Iron Duke made the best of shifting breezes to win the second race, and did so again the following day, both with Lord Jellicoe at the helm. The next two races were in solid sou'westers, and again Heather showed the Aucklanders how to sail on their own harbour. She won the fourth race by a whopping 12m 25s and the deciding fifth race by 2m 7s.

Aucklanders had hardly got a look at the new trophy and it was already heading south.

Photo Courtesy of the Broad Bay Boating Club

The Commodore of the Otago Yacht Club, Mr A.C. Hanlon, struck the right patriotic note stating that '.. besides the honor of winning the Sanders Cup, they could take credit for doing what the Germans in all their strength had never succeeded in doing and that was beating Lord Jellicoe.' The joke was 'keenly appreciated' by His Excellency.

Offers were made for Heather, but her owners refused at any price and she was railed back to a triumphant Dunedin reception, with Wilkinson lamenting that '.. Auckland's inter-colonial reputation for building fast sailing craft has not been justified in this case..'

Despite the loss, the event was a huge success and the 1920/21 Waitemata season was capped off with Vice-Regal attendance at all the club prize-givings. Lord Jellicoe then temporarily relocated to Wellington, took Iron Duke with him, and sparked a similar 14-foot fever in the capital.

Wilkinson now undertook another typically single-minded campaign to have the One Design renamed the `Jellicoe Class' in honour of the man who had attracted so much attention to it. In his weekly Auckland Star columns, he repeatedly made vague references to the `opinions of prominent yachtsmen' who all apparently agreed that it was a good idea. Eventually, he ceased hinting at a ground swell of opinion and simply referred to it constantly as the `Jellicoe Class', as did his good friend at the NZ Herald, George Laycock. With the press sewn up there was no argument, and the `Jellicoe Class' it became.

During the winter of 1921, the Auckland yacht registration system was radically overhauled.

All yacht classes were grouped together under letters, the 14-foot One Design Class being allotted letter X. While now known everywhere else in New Zealand as Jellicoe Class, in Auckland, they would be known as the X-class.

The rash of new boats continued. Another nine were built in Auckland, which brought the fleet to 22. Dunedin built another three, while new fleets were begun in Wellington and Canterbury. By the time the challenge date closed in December, Otago had received entries from Auckland, Wellington, Canterbury and Southland.

After a several inconclusive races, Nyria, skippered by young Vic Lidgard emerged as the front runner in Auckland, but the Sanders Cup selection panel astounded the public by opting for the proven combination of Cloke and Patrick in Desert Gold. Wellington challenged with Iron Duke, Canterbury with Linnet, Southland with Murihiku, while Otago defended with Bill McCulloch and Heather.

In frustrating light conditions, Desert Gold retrieved the Sanders Cup for Auckland, but a dark horse in the form of Carol Hansen's Muruhiku from Stewart Island, representing Southland, gave everyone a run for their money. With no points for placings, just wins being counted, Otago, Auckland and Southland were tied with two wins each going into the deciding seventh race. A hole in the breeze decided the race, and the Cup in Auckland's favor but Murihiku's effort, with little pre-race competition, gave an indication that the southern yachting centers were taking this new-fangled provincial competition very seriously indeed.

That winter, the Desert Gold crew was feted at every yacht club prizegiving in Auckland. Victoria Cruising Club staged an extravaganza at the Town Hall and even had Desert Gold and Iron Duke either side of the stage, fully rigged, and sails hoisted.

A similar gathering at the Dunedin Art Gallery left no doubt as to the effect the Sanders Cup was having in the smaller centres. An address by the Mayor of Dunedin lauded the crew of Heather as `all good sports', and called on other provinces to see that Auckland did not retain the Cup.

`Several other speakers voiced their goodwill, after which Mr McCulloch was presented with an illuminated address and a purse well filled with notes.. in the hope that the money would help build a new boat to regain the cup'. A gold wrist-watch, `suitably inscribed' was given to Mr McCulloch's wife and gold medals to each of Heather's crew from the 1921 and 1922 contests. `On resuming his seat, Mr McCullogh was again cheered, the audience singing "For He's a Jolly Food Fellow"'.

What he would have got had he won?

Meanwhile, back in Auckland, a disturbing trend was emerging. While its administrators and supporters regarded scratch racing in one-design boats as the ultimate competition, it was difficult to achieve. The boats were not exactly the same, and nor were the abilities of their owners. In fleets of twelve or thirteen, it requires a hardy soul indeed to campaign a slow boat, week in and week out, for no reward. Most did not, and soon raced elsewhere.

Beginning with La Ola as early as 1917, unsuccessful One Designs often raced with modified sail area in the 14-foot Handicap Class, (renamed the T-class in 1921). As long as new hulls were being built, it was not a problem, but once that slowed, the Class looked very thin indeed.

Also, the first measurement problems had arisen, an aspect that would plague the class for decades. The original 1916 plans were relatively simple and in many instances called for maximum tolerances, but set no minimums. Several boats had variations of as much as 3 inches less in the width of the tuck, all quite legal under the rules and duly passed by their measurers.

The rules were strengthened by the Auckland Yacht and Motor Boat Association in April 1922, but in seeking their ideal of a strict one design class, they allowed that only boats now complying with the 1922 rules could race for the Sanders Cup. All hell broke loose.

Most of the Auckland fleet, including crack boats such as Nyria, could not obtain a new certificate without major reconstruction. Even worse, several sets of plans sent south, had not been amended, and boats had been built to them. Clarification was sought, and prospective owners put building plans on hold pending the outcome.

The AYMBA refused to budge. The winter of 1922 was taken up with meetings, threats, counter-threats, and a complete lack of will on the part of anyone to build new boats.

Auckland was on a collision course with the rest of New Zealand. For the first time, rumblings arose from the south of the need for a `Dominion Yachting Council' to take over the Sanders Cup and control its rules and competitions. For the first time, but not the last, Auckland would ignore them.

There was genuine surprise at the strength of feeling `south of the Bombay Hills', but the implication that all they had to do was build new boats, enraged not only the southerners but most Auckland owners as well.

The AYMBA huffed and puffed, and trotted out the Deed of Gift that vested the Cup in their care alone. Meanwhile in his Star column, Wilkinson continually invoked the `heroic memory of Lt.Cdr. W.E. Sanders VC, the bravest yachtsman the Dominion has ever known', as a sterling example of the type of pluck needed to support the 14-foot class in its hour of need.

Both posturings had little effect.

Reluctantly, and under immense pressure from owners, clubs, and Provincial Associations alike, the AYMBA compromised and deemed all existing boats were eligible to compete in the next Sanders Cup. A sigh of relief went up around the country.

The Auckland selection trials were a foregone conclusion. Prominent RNZYS member, Alf Gifford had approached Arch Logan to build a 14-footer, but Logan refused outright (he remarked that `they would be nothing but trouble'). Surprised but undaunted, Gifford went to Charles Bailey junior.

Rona was launched too late to sail in the trials that saw Desert Gold selected for the 1922 Sanders Cup series, but for the rest of the season, with 18 year old Jack Gifford at the helm, she dominated the class. Her ten wins, four seconds and three thirds from 17 starts, tipped her as the next likely defender.

Much to Jack's disgust, his father regarded the Cup trials as too important to be left to a youngster, and replaced him with the experienced Alex Matthews. Rona easily won the selection, romping home in almost every race. Even so, there was great concern over the perceived southern threat, and the AYMBA deliberated for several weeks over her crew. Eventually, Alex Matthews was chosen as skipper, along with NINE other nominated crewmen (including Jack Gifford, with Vic Lidgard as the light weather skipper). Overkill indeed for a three-man centreboarder.

The Cup races began on the Waitemata late in January 1923, with a surprise victory to the Canterbury boat Linnet sailed by Sam Sinclair. The next race was not much better, Tom Bragg in the Southland entrant Murihiku, taking the gun by 45 seconds from Vic Lidgard in Rona. All Auckland was worried.

The next three races were in fresh to strong breezes and Rona just blitzed the opposition, winning by margins of 3m 40s, 8m 39s, and 14m 14s. It was a comprehensive thumping. To Auckland's relief, the Sanders Cup remained there.

Prior to the Cup races, the provincial delegates had agreed in principle to accept Rona's lines as the basis for a strict one-design class, and thus remove any further arguments over rules. Her superiority during the contest swept away any misgivings, and the remit was passed before the end of the month. The Rona-Jellicoe class had been born.

Aucklanders, typically however, refused the unwieldy moniker and continued to call them, the X-class.

Part 3: Rona to Betty

The 1923 ruling to stabilize the Jellicoe Class around Rona's lines was a sound move nationally, but achieved little in Auckland. The clear superiority of Desert Gold, Iron Duke and latterly Jack Gifford's Rona had driven all but the keenest competitors into the handicapped T-Class, a class that Wilkie Wilkinson sniffily referred to as a `class for second raters'.

Just one new Rona-Jellicoe, the Queen March, was launched for the 1923/24 season. She was built by Baileys for Eliot Davis, brother of Ernest, and was named after his champion racehorse. With Alex Matthews as skipper, Queen March was thrown into the Auckland Sanders Cup trials against Joan and Rona. She failed to impress. Rona again dominated and won selection.

The previous season, Rona's 18 year old skipper Jack Gifford was deemed too young to take on the heady responsibility of defending on behalf of Auckland, despite his domination of the pre-trial racing (interviewed in 1998, and a cheerful and alert 95 year old, that decision still rankles him). This time, the selectors opted to remain with him as skipper, he had won 22 out of his last 28 races, and even Wilkinson demanded that they `get a good man and stick to him'.

The 1924 Sanders Cup contest was held in Wellington. Opposing Rona was Canterbury's Linnett, the redoubtable Murihiku from Southland, Peggy from Wellington and two new Rona-Jellicoe hulls, June, from Otago, and Konini from Hawkes Bay, the latter being manned by the veteran Hawkes Bay patiki men, Neil Gillies, Len Turville, and Allan McCarthy.

The first race was a disaster. A severe squall hit the fleet just after the start. All contestants were either planing at high speed, in trouble, or both, as one reporter described how `..Konini raced down Evans Bay, with her spinnaker skying to the top of the mast, and her bow completely out of the water. She tore along in this fashion and then ploughed under, spilling her crew in all directions.' Only Rona survived. She continued on alone, beating back into the hard southerly breeze, carrying full sail and a four-man crew. Jack Gifford was not amused when the officials called the race off. Fittingly, Rona won the resail.

Murihiku took the second race. Rona won the third race but was disqualified for fouling both June and the starters boat. Gifford made no mistake with the next two races winning them by 36 seconds and the final, in light shifting airs, by a whopping 22 minutes from Linnet (although at one time Linnet was 12 minutes ahead of Rona!). Winning two consecutive Sanders Cups, firmly cemented Rona into Cup mythology as the first `super boat'.

Murihiku took the second race. Rona won the third race but was disqualified for fouling both June and the starters boat. Gifford made no mistake with the next two races winning them by 36 seconds and the final, in light shifting airs, by a whopping 22 minutes from Linnet (although at one time Linnet was 12 minutes ahead of Rona!). Winning two consecutive Sanders Cups, firmly cemented Rona into Cup mythology as the first `super boat'.

While the other representatives returned to their provinces determined more than ever to win the trophy, Rona returned to a class still in disarray. Her triumph was feted as usual, and the trophy proudly displayed at homecoming `smoke concerts' but Rona's success belied the rapid decline of the Auckland X-class fleet. Only Rona, Iron Duke, Queen March and occasionally Idler saw out the rest of the season. The others were either up for sale, sold out of Auckland, or converted to the handicap T-Class.

In Auckland, unlike elsewhere, the X-class competed with a wide variety of other centreboard classes. The AYMBA and both daily papers towed a distinctly pro-X-class line, and the undue prominence given to the 14-footer at the expense of other far more popular classes was the cause of considerable backlash at club level.

As related in this column last month, the arrival of Lord Jellicoe had certainly been the main reason for the involvement of the Royal New Zealand Yacht Squadron. As Jellicoe himself became less and less involved, and the AYMBA's intransigence over aspects of the rules alienated many yachtsmen, so too did the Squadron withdraw more from the X-class.

In 1923 RNZYS had adopted Arch Logan's 18-foot Restricted Patiki class, a modernised version of the old Restricted Patiki (See Boating NZ August 1998). Logan had refused any involvement in the fashionable 14-foot class and his new patiki can be seen as a direct counter to what many saw were the excesses in the X-Class, that had taken it away from its original concept as a youth trainer.

The patiki, designated the M-Class, was intended to supplement the Squadron's 14-footers, but inside two years it had replaced them. Being completely under Squadron control, the M-Class remained aloof from the arguments, pettiness, professionalism, and the many uncompetitive boats that dogged the 14-foot class, and many prominent squadron members supported it. Even Jellicoe himself, in a farewell speech had said (supposedly in jest), that his successor should take up the M-Class because `there are no blanks in this class'. Such a remark must have stung.

During the winter of 1924, Lord and Lady Jellicoe made their rounds of the various yacht clubs in preparation for their return `Home'. From the reported fond farewells, and the high standard of gifts presented to them, there was clearly a genuine regret, and a feeling that something quite special in New Zealand yachting was about to end. It was made more solid by a gesture that touched all Auckland yachtsmen, when Jellicoe gifted Iron Duke to his long-standing crewman Andy Carnachan.

In October that year Lord Jellicoe departed and with him, the spark went out of the Sanders Cup, particularly in Auckland.

The Auckland preparations for the 1925 defense on the Waitemata garnered little enthusiasm locally, although the provincial associations again mounted their intense and parochial challenges. Auckland's defender, Queen March was never in the hunt. The Otago challenger Iona, skippered by Alf Wiseman sailed over and under everybody in three races out of four to win the Cup in the fastest series thus far, just one race being won by another contestant, the indefatigable Southlander Carol Hansen in Murihiku.

Iona's win however, begat yet another round of controversy. She was not a `Rona-Jellicoe', but was built to the old rules and permitted to race under the AYMBA's ruling of the previous year. Did this mean (Shock! Horror!) the old designs were actually faster than the `Rona-Jellicoe' type, the new class standard? For months and months this point was debated ad nauseum, the length and breadth of the country, prompting a brief revival of older pre-Rona boats.

Auckland's waning interest in the X-class was briefly stirred by the news that class stalwarts Cloke and Patrick had commissioned a new boat from Baileys, to be named Avalon. Wilkinson's columns in the Auckland Star were ecstatic. Rona had been sold, and was not nearly as competitive, and Queen March had proved an erratic performer. Such was the reputation of Avalon's owners, that almost before she was launched, her selection was a foregone conclusion. The 1926 contest in Dunedin was eagerly awaited.

Otago defended with the champion Iona, but amid considerable dissent, as many felt that their newest boat Winifred, a true Rona type, was the better choice. Again, Napier challenged with Konini, Southland with Murihiku, and Wellington with Peggy.

Canterbury was last to name their representative. All their previous challenges had been Lyttelton based affairs, and their selection was expected to be between two new Lyttelton boats, Fred Morrison's Secret and Sam Sinclair's Linnet II, but things do not always go as expected.

A newcomer to the Sanders Cup Class, George Andrews from the Christchurch Sailing and PowerBoat Club, easily beat the other triallists in a boat designed and built by himself, named Betty. The Lyttelton factions were not amused.

In general, yachtsmen from `the Port' scorned the `mud hoppers' who sailed on the other side of the Port Hills with the tidal Estuary yacht clubs. It seemed inconceivable that an Estuary amateur could design, build and then sail his boat to victory over their professionally commissioned ones. Despite the fact that Betty measured, and was re-measured in every way, the idea persisted that somehow she was at best `a freak', at worst, `not a true Rona-Jellicoe'.

The Canterbury Association delayed announcing their challenger but finally permitted Betty to represent them in Dunedin, with an assurance from her sponsoring club, that should she fail measurement, they would meet the cost of having her shipped down there. Such doubts would provide fuel for others.

Otago expected a strong challenge from Auckland and this was confirmed when Avalon easily won the first race in light and fickle breezes. The next race, in a stiff breeze, brought out the best, not only in Avalon but also Betty who fought board for board with her, both leaving the rest well behind. Avalon capsized in one of the many squalls that swept the course and left Betty to take the gun by over 12 minutes from Murihiku and Konini. Otago's Iona retired with broken gear.

Under the contest rules, all provinces that had not taken a gun after three races were eliminated and when Betty comfortably won the third race, Wellington, Southland, Hawkes Bay, and the holders, Otago were cut from the series.

Now reduced to a `match race', Avalon evened the score, winning the fourth race in a strong southwest gale. The fifth and deciding race, over a windward-leeward course six times around Castle Beacon, was a real thriller and regarded by reporters as `the finest race ever sailed for the Sanders Cup'.

In breeze that veered between south-west and south-east, Betty got away from Avalon and for the first five marks, held a narrow lead, never any more than 11 seconds. Avalon closed to a boat length, tacked on a lift and gained the lead, to be 34 seconds ahead at the next mark. She held that lead for three legs, but as the breeze increased, Betty whittled it away and came to within 3 seconds the flat run. Betty broke tacks as soon as they rounded and lifted away. When they next crossed, Betty had regained the lead and held a 22-second advantage. For the rest of the race, Betty `camped' on Avalon, eventually taking the gun by 41 seconds, and with it, the Sanders Cup.

Delerium broke out. Betty and her crew were ` loudly cheered from wharf and steamers, whistles tooting'. A ferry steamer with Christchurch school children on a harbour trip passed her and `from the youngsters was eight vigorous cheers'.

Not only was it the first success for Canterbury, but George Andrews was the first to win the Sanders Cup in a boat designed, built, owned and sailed by himself.

In Canterbury, any acrimony over Betty's selection was lost in the clamour. Ironically, the doubts that were now conveniently forgotten by Cantabrians were taken up wholeheartedly by others, particularly in Dunedin, where the poor showing of Iona and her early elimination, was a very sore topic.

The 1926 contest, once and for all, settled the argument over whether the strict one-design Rona-Jellicoe was superior to the older type, but the debate shifted and became more heated. What was a true Rona-Jellicoe? One Dunedin writer maintained that Betty could not be true because she was amateur built and even inferred that Avalon was an `unfair boat'.

Comments like that brought Wilkinson out in a foaming frenzy. He deplored the poor sportsmanship emanating from Dunedin and commended all the ` …real sports who join heartily with Auckland in giving Betty and her plucky owner, builder and sailing master full credit for his great exhibition of skill and endurance which won him the "blue riband" of Inter-Provincial yachting for 1926. Let us hear no more about "unfair boats".

His plea had little effect. The great Betty controversy was now well under way and would be a lively discussion point for many years to come.

Part 4 - George Andrews and Betty

The furore surrounding George Andrews and Betty's win in the 1926 Sanders Cup contest in Dunedin, did not so much die down as simmer (See Vintage Viewpoint November 1998). Rumour and innuendo, sometimes of a personal nature, continued to bubble up from the South. Betty, was `not a true Rona-Jellicoe', she was `too fine', `too full'.

If there were any genuine irregularities, they were not obvious and her detractors could only speculate on some vague `unfairness' about her, to rationalise her successes. To them, it seemed well nigh impossible for an amateur to design such a boat, let alone build her; sail her and so comprehensively beat the professionally built hulls. She had to be illegal, for nothing else made any sense.

Aucklanders largely remained above the debate, which was essentially a southern affair, but were quite taken aback by its intensity. AYMBA members, E.J. `Manny' Kelly and Charles Palmer, on their return to Auckland following the contest deplored the criticism levelled at Betty and her owner-skipper, who had been dubbed `a farmer'. In the parlance of the old style Edwardian yachtsmen, to be called a `farmer' was a most derogatory term indeed and implied a sort of uncultured, unseamanlike approach to the noble sport of yachting.

By a peculiar twist, calling Andrews `a farmer' was almost accurate. During the 1920's he owned a tomato garden in the Heathcote Valley and had an interest in a West Coast dairy farm, so such a remark was probably intended as feeble joke. However, amid the indignation and rhetoric, it seems likely that his supporters assumed the worst, that a fine yachtsman was being grossly insulted.

It was ironic given the same Edwardian attitudes to professionalism that had racked the sport for many years, and the number of professionally built boats in the Jellicoe Class, that the venom was directed at the only truly amateur campaign in the entire competition.

The man at the centre of the storm, while largely unknown in the north, was already a legend in Canterbury. George Grey Andrews, named after his father's close friend, Governor Sir George Grey, was born in 1880 and spent his early years messing about in boats on the Christchurch Estuary. He built and raced dinghies and punts of his own design, and for many years competed with distinction in the busy Estuary scow scene with the Christchurch Yacht Club.

During the First World War he was attached to the hospital ship Maheno as officer in charge of the ship's launches evacuating the wounded from Gallipoli. He later gained a commission in the RNVR engaged in the Dover Patrol, in the North Sea and operations out of Great Yarmouth. He had earlier served an apprenticeship as an engineer and by War's end had obtained a third class marine engineer's certificate. At the end of the War, he returned to Canterbury and his hobby of small boat design.

In the many articles written about George Andrews' yachts, one factor is common and that is his emphasis on weight reduction. From his champion 16-footer Ariti, through Betty, and his infamous Zeddie Gadfly, which won every race in the 1927 Cornwell Cup competition (with a different crew sailing her in every race), Andrews attributed their successes in no small way to his attempts to achieve a minimum weight.

This type of thinking is commonplace today but at the time, hull weight in small boats was not considered particularly important. Even Wilkie Wilkinson, a strong Andrews supporter, professed himself to be `impressed with the fact that her skipper attributed her wins to this lightness', as if it was somehow unbelievable. In this approach, Andrews was probably well ahead of his time and more akin to the type of thinking Uffa Fox was then engaging in, half a world away.

Many years later in an article for Sea Spray, Andrews with hindsight, had this to say,

`[Betty's] only feature of note was that she was lighter than most of the others. I wanted a boat that would always be good off the wind, where the boat had the most say, and which would rely on the crew and trickery to get her to windward.

In our first season in the class we had no time to get familiar with the feel of the boat and we had nothing to spare in our first contest in Dunedin. In the next two contests we could play with the other boats. Having the legs of them on or off the wind we could dawdle among them or let one have the lead at the last mark to make it look close racing.

The only race I recollect in which Betty was sailed all the way with conditions that suited her was the [Canterbury 14-foot] championship race at Lyttelton in 1927. In a fresh flawless breeze she finished 11 minutes ahead of the next boat.'

While much has been made of Betty's lightness, she was built in kauri like all the others, it was a class rule, so any gross under building should have been obvious. Yet there was never any suggestion, even from her critics, that she was markedly different in weight and scantlings.

If she were truly light, she would have run away from all the opposition off the wind, yet in several of the Cup competitions, she was run down off the wind, and did not win every race by huge margins. The Sanders Cup races, with one or two notable exceptions, were hard fought campaigns, all around the course, and of Avalon, Rona and Betty, neither appeared to have any particular advantage over the other.

During a recent interview, Jack Gifford, who travelled to those Cup contests as an observer, recalled George Andrews as being a quiet, unassuming man and `a thinker'. In Gifford's opinion, Betty and Avalon were the ` two best prepared and finished boats in the competition. There was nothing wrong with Betty, she measured and she was sailed exceptionally well.'

We suspect there may well have been significant weight differences between Betty and some of the Canterbury boats she defeated during the trials and in club races. Alongside her two great rivals Avalon and Rona, which were the only boats that regularly troubled her, there was probably very little difference. In fact the Aucklanders, rather than display the outrage of her southern competitors, treated Betty and her owner with the respect deserving of a tough and skilful competitor.

Many years later, George Andrews told Graham Mander that it was Betty's sails that gave her the edge; their cut, and the care he took in their setting. Andrews already had a reputation on the Estuary as a brilliant helmsman. He had now shown his superiority, not only over the `harbourites' at Lyttelton, which is how the Betty controversy started, but over the best in the Dominion as well. Perhaps, given his well-known reluctance for self-promotion, he allowed the boat to take all the credit, rather than tell everyone how well he had tuned her and how cleverly he had sailed her.

The 1927 Sanders Cup series was sailed on Lyttelton Harbour. Betty again dominated the local triallists and won the right to defend for Canterbury. Her opponents were a mix of old and new. Two restricted pre-Rona designs were present. Peggy again represented Wellington, while Otago challenged with the Winifred, the boat many thought should have represented Otago in the previous contest.

The Auckland scene was again in a state of flux. Many Waitemata clubs were extremely reluctant to pay the AYMBA-required Sanders Cup levies for a class that was so poorly supported. Others were disheartened by the unpleasantness arising from the previous series, and continued calls from Wellington and Otago to abandon the one-design ideal and return to a restricted class.

Only two boats, Joan and Rona had contested the Auckland trials and Alex Matthews skippering Rona was selected. Avalon's owner, railwayman Frank Cloke, on transfer to the Hawkes Bay region, offered Avalon as their representative. Southland was there again, only this time the Stewart Islanders had a new Rona-Jellicoe design, named Murihiku II, built that winter by Glad Bailey.

Avalon, Rona and Betty were the only boats to show any form. Betty won the first race handsomely, while Avalon took the second, passing Betty downwind on the last leg to win by 8 seconds. Betty won the third, by a minute from Avalon.

In what has been described as a grand show of sportsmanship, but was also a display of supreme confidence with two wins in the bag, Andrews handed the tiller over to 18 year old Ian Treleaven for the fourth race.

In a building breeze, Rona all but ran away with the race but Betty, under young Treleaven, kept coming back at her. On the downwind leg to the finish, both were neck and neck and, as the Christchurch Press described it, "wing level with wing came Rona and Betty fairly booming down the wind. Sometimes Rona would poke her nose in front, sometimes Betty. A few yards from the line, Rona picked up and drew slightly ahead and in a dashing finish won by 2 seconds."

The final race was another struggle between Betty and Rona. Betty made the early running but Rona caught and passed her on the final upwind leg to round 15 seconds ahead. Betty got ahead by a length or two and another grim downwind battle took place with Rona unsuccessfully trying to blanket Betty who ran out the winner by 18 seconds, to take the cup for a second time.

Apart from being Andrews' second triumph, it was yet another emphatic victory for the Rona-Jellicoe supporters. Even Murihiku II, which had barely been in the water a week and lacked tuning, totally outclassed both the restricted boats Winifred and Peggy.

The congratulations had hardly subsided before the rumours about Betty's alleged irregularities arose again. At the Dominion Conference, the rumblings again came from Otago and Lyttelton where, as the Press reporter said, `there appeared, however, to be a strong undercurrent of jealousy between Lyttelton and Christchurch.' This time the doubters even went as far as implying that Rona, the prototype was not a true Rona-Jellicoe according to the plan.

Auckland's Wilkie Wilkinson again defended Betty's measurement certificate. Once again he went into print, waving the Union Jack and retelling the dramatic story of plucky young Sanders and his VC, reminding delegates that this memorial to Sanders' heroism, should not be cheapened by petty squabbles. It all got rather messy as delegates postured and pontificated yet again, over just what was a true Rona-Jellicoe. It was even agreed that a Dominion measurer be appointed to measure all boats three months out from future contests, but nothing came of it.

The conference did, however, recognise the sterling efforts from the Southland men who, in the last six contests, had travelled some 6000 miles to compete. The 1928 series was set down for Paterson's Inlet on Stewart Island, Murihiku's home waters.

Delegates returned to their provinces and began to dissect the respective successes/failures of their campaigns, and make plans for Stewart Island.

Part 4 - George Andrews and Betty ... Conclusion

In the months that followed the 1927 Sanders Cup, the Betty measurement saga rumbled on in ever more tedious fashion, kept alive by accusers and defenders alike. Infuriatingly, no one actually did anything, other than insinuate and make vague generalisations based on both their own, and received, "expert knowledge". In the history of New Zealand yachting, we doubt whether there has ever been anything more tiresome than the Sanders Cup measurement wrangles, and none more so than those that surrounded Betty. (Oh, except for the Moffat Cup measurement disputes of the 1950's - remember the `Outcry batten'?).

The Otago Association even made veiled threats that they would not enter the next contest. This stance eased somewhat during the winter of 1927, when they requested a complete set of plans, stamped as being correct, to the latest set of restrictions. Given the problems they had experienced back in 1922 when they were provided with obsolete plans, this was perhaps understandable. Their request was complied with and the plans that had produced Avalon and Murihiku II were sent south.

Aucklanders luckily, were spared the excesses of the Betty saga. Their main problem was that apart from Wilkie Wilkinson and a few others, no one in Auckland cared a fig for the Sanders Cup. The Auckland selection trials were notable for the desperate panic to commission any boat fit enough to start with Avalon, let alone race against her. Wellington challenged with a new boat Wellesley II, like her predecessor, built for the members of the Wellesley Club, while Otago's new boat, was named Eileen, although the local wags reported that it was named OLC (Otago's Last Chance). Southland challenged with the locally owned Murihiku II.

Apart from a fine win by Avalon in the third race, Betty swept all before her. Only in the last race was she really pushed, as Joe Patrick in Avalon forced the pace in a do or die effort to remain in the contest. Both left the rest of the fleet in their wake. Betty took the gun by 16 seconds from Avalon, with 5m 29s back to the next boat, Eileen. George Andrews and Betty had won their third consecutive Sanders Cup.

Almost immediately, Andrews announced that he would retire from future Sanders Cup competitions. Having won three in succession, he felt that interest in the contest would fade if Betty won a fourth. There were genuine expressions of regret from all provinces, although there must also have been a degree of relief.

After a seasons lay-off, in which Auckland's Avalon under A.L.'Trotter' Willetts won the 1929 Sanders Cup at Akaroa, George Andrews' crewman, Ian Treleaven brought Betty out of retirement. She won the Canterbury selection trials for the 1930 competition in Auckland, but when the Canterbury Yachting Association wanted the final say in crew selection, Treleaven refused to break up his crew and accept the Association's nominees. The Association bypassed Betty and sent the second placed boat Colleen instead.

To prove a point, Treleaven took Betty to Auckland anyway. The 1930 Auckland Anniversary Regatta, had scheduled two open X class races for the Lipton Cup and the Ross Cup. As well as the local boats, all the Sanders Cup representatives entered. Avalon won the first race, but later withdrew after her skipper reported fouling a mark, allowing Betty the honours. Betty won took the gun in the second race and annexed both cups.

Later that week, Ian Treleaven and his crew watched Otago's Eileen win the Sanders Cup with ease; Canterbury's Colleen was never in the hunt at any stage.

Following the Auckland Regatta, a syndicate headed by Mr.J. Moffat of Wellington purchased Betty and took her to Port Nicholson.

In Auckland that winter, the whole concept of the Sanders Cup came in for intense scrutiny. Such was the apathy toward the competition, that if any challenge was to be mounted for Dunedin in 1931, the only boat up to to any standard, was Avalon.

At a meeting of the AYMBA in December 1930 the discussion centred on how far the class had drifted from its original 1916 concept of a youth trainer and young man's boat. Several clubs declined to contribute to the expenses unless young men were put into Avalon and the committee concurred. For the first time in the history of the Sanders Cup, a boat was to be sailed by boys under 21. Doug Rogers, Bill Tupp jnr, A.H. Larritt and R. Andrews were selected and went south.

They were very unlucky. Two races were abandoned at the three-hour time limit, with Avalon leading, just short of the finish line. A disqualification and a withdrawal in other races ruined any fairy-tale outcome.

Betty, representing Wellington and skippered by Alan `Cooee' Johnston, gave the Capital their first ever Sanders Cup win, defeating her old adversary Rona, which this time represented Southland, Colleen of Canterbury and last years champion Eileen. Following the competition Avalon was sold to Percy Hunter of Port Chalmers.

Under the headline `Wellington "buys" the Sanders Cup', Auckland's aquatic newspaper `The Pennant', after lauding the performance of Avalon's young crew, took a sarcastic dig at Wellington's Sanders Cup fanatics.

`Now there is no whipping the cat to point the obvious truth that Auckland yachtsmen in the main care little whether the Cup stays South for all time. A good deal has been said about Betty but as Auckland did not recapture the trophy there is every wish to avoid uncharitableness.

But this fact emerges clearly. Wellington has crowned a ten years' ambition by acquiring Betty from Canterbury by the syndicated expenditure of a few pounds cash. A cynical observation invades the mind. It is this: Auckland has lost Avalon…some of us want the Cup back….we offer Wellington a couple of hundred Betty…we sail Betty, and lo! Back comes the Cup.'

Auckland didn't buy Betty and they didn't regain the Cup. In 1932 they challenged with a veteran crew, in a veteran boat Rangi, built in 1921. It was a miserable combination.

Betty however, almost did it again for Wellington. With the series tied at two races each between Betty and Avenger from Canterbury (sailed by the redoubtable George Brasell), Betty capsized while leading in the decisive fifth race. Avenger took the Cup to Canterbury.

That was Betty's last Sanders Cup race. Little is known of her later movements until 1953 when she is recorded as being down in Bluff, owned by D. Perkins. Betty was last seen, in derelict condition, on a beach in Stewart Island in 1967.

Of her great rivals, Rona and Avalon, Rona was sold to Tom Bragg of Stewart Island in 1930 and was Southland rep in the 1931 Sanders Cup. She was still down that way as late as 1953 owned by W. Dawson of Invercargill and registered there as X-6.

Avalon had represented Auckland in six consecutive Sanders Cup competitions from 1926 to 1931, with a single victory in 1929 at Akaroa, the year after Betty's retirement. She was sold to Port Chalmers in 1931, and represented Otago in the 1933 competition. That same year, Mr. A. McKenzie of Wellington purchased her, renamed her Monica, and represented Wellington in the 1935 contest. By 1945 she had been renamed Cedric and was based in Wanganui and owned by B. Armit. She became the Wanganui representative in the 1947 Sanders Cup held in Auckland. That competition was won by A.L. `Trotter' Willetts in Dianne, who 18 years earlier, in 1929, had skippered Avalon to her only Sanders Cup success.

After his retirement from the Sanders Cup, George Andrews returned to the less public life of Estuary sailing and building boats. During his lifetime, he built over sixty boats, some of them quite significant, such as Mandalay, a 40-foot ketch built in 1931 to his own design, in which he cruised the Marlborough Sounds. `Wilkie' Wilkinson bought her around 1943 and in 1948 sold her to the Methodist Mission in the Solomon Islands.

During the mid 30's Andrews went to Stewart Island, to complete the building of Ranui, a 66-foot auxiliary ketch on which construction had halted after her builder left New Zealand. Ranui was launched in 1936 and until the outbreak of war, carried fish and other cargoes between Port Pegasus and Bluff. After the war, she serviced the meteorological stations on the Auckland and Campbell Islands. Following many years as a crayfisher and an oyster dredger, Ranui has recently been restored and is returned to her original ketch rig.

In 1939, Andrews built the 31-foot Varuna, a light displacement W. Starling Burgess design, known in the United States as the Yankee One-Design class. By 1962, Varuna had arrived in Auckland and registered as C-27, later NZYF number 1227.

As well as designing and building the M-Class Malay in 1934 (recently rebuilt and back sailing again), he also helped popularise another major centreboard class. His D-Class dinghy Rita also built in 1934 became the first of a new class, the Canterbury T-Class formed in 1937. The T-Class was a 12-foot 9-inch round bilge dinghy with an unrestricted hull design, but with a restricted sail area of 110 square feet. Probably to avoid confusion with North Island 14-foot T-Classes, they became known as the R-Class in 1948, Rita becoming R-1.

Without a doubt, George Andrews influenced several generations of Canterbury yachtsmen, in particular those youngsters who began their sailing during the 1940's. By then, he was an old man but still more than capable of showing the youngsters a thing or two out on the racetrack. He advised them, he tutored them and he helped them build their boats, P-class, Silver Ferns, Frostbites, Takapuna's and even the odd X-Class, and paved the way for those relentless assaults by Cantabrians on our national yachting trophies during the 1950's.

George Andrews died on January 19, 1952 aged 70.

Footnote No.1 :

In 1932, the Sanders Cup conference authorised construction of a full sized external steel mould, to be placed over each boat before the contest. Writing to the Christchurch Press in 1932, Arthur Johnston advised that `the official measurers … in the presence of a referee, Captain Keen of the Marine department, measured the Sanders Cup champion Betty with external steel moulds and the boat passed the test creditably. .. and that the honour of the builder and Canterbury skipper, Mr. George Andrews is vindicated.'

He went on to refer to the `despicable insinuations made by certain Canterbury delegates' and hoped that they would `would express regret for their unfounded statements that have been made in an endeavour to put Mr Andrews offside in the eyes of the New Zealand public.''

Footnote No.2 :

Rona, the champion X-class whose lines were adopted in 1923 as the one-design for all future Sanders Cup competitions, and gave rise to the name, Rona-Jellicoe Class, was found to be `sadly astray in her measurements'. She could not fit the external steel moulds that had been built from her own lines.